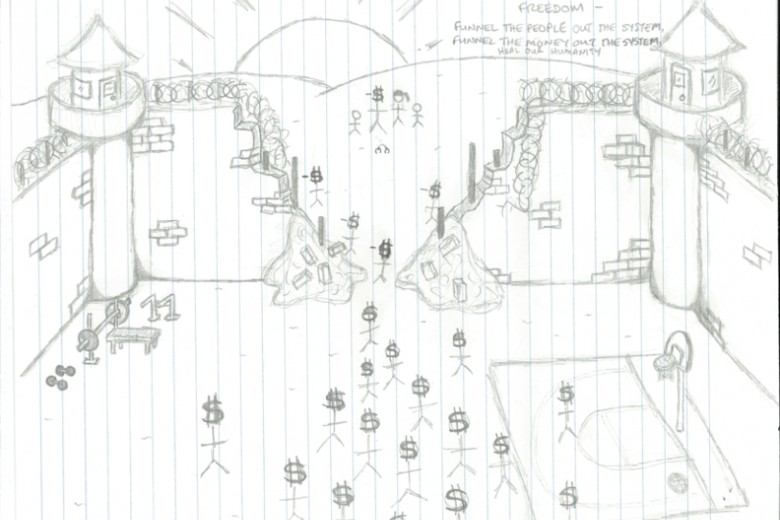

The justice system is rooted in colonial policies that were designed to suppress and control a vulnerable demographic of Aboriginal people so Euro-settlers could profit from the land. These colonial policies support the capitalist agenda of the modern economy, which is built on a campaign of incarcerating a suppressed demographic.

The police build their careers on a system of arrests to meet informal quotas. This system of earned incentives supports arresting (i.e., “reaping”) a harvest of vulnerable people from the margins (“field”) of society. The arrests (“produce”) are then sent to the courts for judicial processing. The judicial court system has cultivated colonial policies adopted from a British legal system to suppress and control Aboriginal people so as to protect and control the interests of a capitalist society.

It is commonly known that Aboriginal people are overrepresented in Saskatchewan’s jails; along with Manitoba, the province has the highest rate of incarceration of Aboriginal people in all of Canada. Aboriginal people make up 16 per cent of our population, but they constitute between 75 to 90 per cent of the provincial prison population, depending on the estimate.

The correctional system is based on an economic structure where the inmate (“product”) is kept in a warehouse, shelved in an institution, fed by a privatized company, the cost-effective solution to provide for the inmate (“product”).

In this process, the rights and humanity of the common inmate are eroded. These rights have been progressively extinguished since the Saskatchewan Party government introduced prison reform in the 2010s.

The correctional system is based on an economic structure where the inmate (“product”) is kept in a warehouse, shelved in an institution, fed by a privatized company, the cost-effective solution to provide for the inmate (“product”).

I remember it well:

Overcrowding was already prevalent before budget cuts to food services. Our food supply was slashed, which created an atmosphere of hunger and depression.

Our clothing was replaced with institutional government clothing, replacing our individualism with a uniform of discrimination.

Our communication was heavily restricted through the introduction of a privatized phone company from Texas called Telmate. Telmate makes more than a million dollars each year off of phone calls from Saskatchewan inmates.

Profit-driven phone prices and predatory fees strained inmates’ families, exacerbating poverty and isolating the inmates from their family and support networks.

I remember inmates sacrificing food in exchange for phone calls and then getting reprimanded for sharing phone PIN numbers. You know it’s real when you must choose between food or family. On top of that, mail communication from family and friends is restricted, which infringes on our Charter right to freedom of association and only isolates us further.

Then there is Compass food services, another privatized company with a profit-driven agenda. It was introduced in 2015 as a cost-effective solution to feed inmates, and it reformed and restricted the canteen, inflating the price of highly sought-after items.

I remember inmates exploiting each other for food on Saturday and Sunday mornings because the Compass menu does not serve breakfast on weekends. Inflated, profit-driven canteen prices create division and a stingy atmosphere. Many inmates are reluctant to share, and they exploit each other for Cheezies and noodles. In the blind spots where guards cannot see inmates fighting over food, the violence is exacerbated. Inmates fight each other over scarce resources, while those who run the system profit. Inmates are exploited, and this forces them to exploit each other.

Very few inmates have paid jobs. Those who do are paid as little as $1 a day. Further cuts to these jobs, which were a small but important “privilege,” collapsed the small inmate economy used to support the inmate committee, our collective representative body. As workers, we are exploited, propping up the system that turns us into products for colonial gain.

We must not forget the persistent overcrowding. I remember the urgency that filled the Saskatoon Provincial Correctional Centre in 2015, with inmates sleeping on floors and urinating in milk jugs in the corner. Inmates needed to have permission to urinate and were refused because it interfered with the movement policies of the institution. This scenario still exists today on living units where inmates must press a button on the wall for permission to urinate. Even with the thousands of dollars spent on renovating these units, they forgot to install toilets in the stalls.

You know your rights are non-existent when you must ask for permission to urinate.

These are just a few examples from the progressive ongoing campaign to diminish our humanity. We are like objects isolated in a warehouse, used as commodities to structure and sustain an economy built on the backs of our suffering Aboriginal inmates, who are caught in cycles of recidivism. Keeping the prisons full sustains this economy, which keeps the common correctional officer employed, in order to feed their families. We as inmates have become job security and a valuable resource for anyone employed within the correctional system, putting in 25 years, working toward securing a pension.

If the prisons were empty, there would be no employment.

Remembering Cory

Cory Charles Cardinal was a Cree poet, spoken word artist, and prisoner justice advocate. On June 9, 2021, he passed away from a drug overdose two months after his release from the Saskatoon Provincial Correctional Centre. Cardinal’s death is the direct result of the settler colonial systems – including foster care, policing, and prisons – that are designed to remove Indigenous Peoples from their lands, cultures, and kin. His article in this special issue is the culmination of many years of advocacy and insight into the predatory design of the penal system, which benefits settler colonial possession at the expense of Indigenous lives and lands.

In 2015, Cardinal founded Inmates 4 Humane Conditions, a prisoner advocacy group that began in response to the privatization of food services in Saskatchewan jails and, since then, has continued to mobilize prisoners to unite in collective defense of their rights. Over the past year, Cardinal organized several multi-institution prisoner hunger strikes and letter-writing campaigns in response to the Saskatchewan government’s gross indifference to the wellbeing of incarcerated people during the COVID-19 pandemic. He also galvanized the support of outside advocates, understanding that robust circles of non-carceral care must connect people inside and outside prison walls. His work, as he explained to us, was an “act of love” in “defense” of his people.

Through direct action, education, and solidarity, Cardinal invited us to work together as relatives to remember and create a world beyond prisons, a world where care and compassion are extended to everyone. Animated by a passionate desire to “protect the people,” Cardinal gifted us with an anti-colonial abolitionist vision of how to take good care of our relations through love and resistance. Let us continue this fight in his honour.

—Free Lands Free Peoples